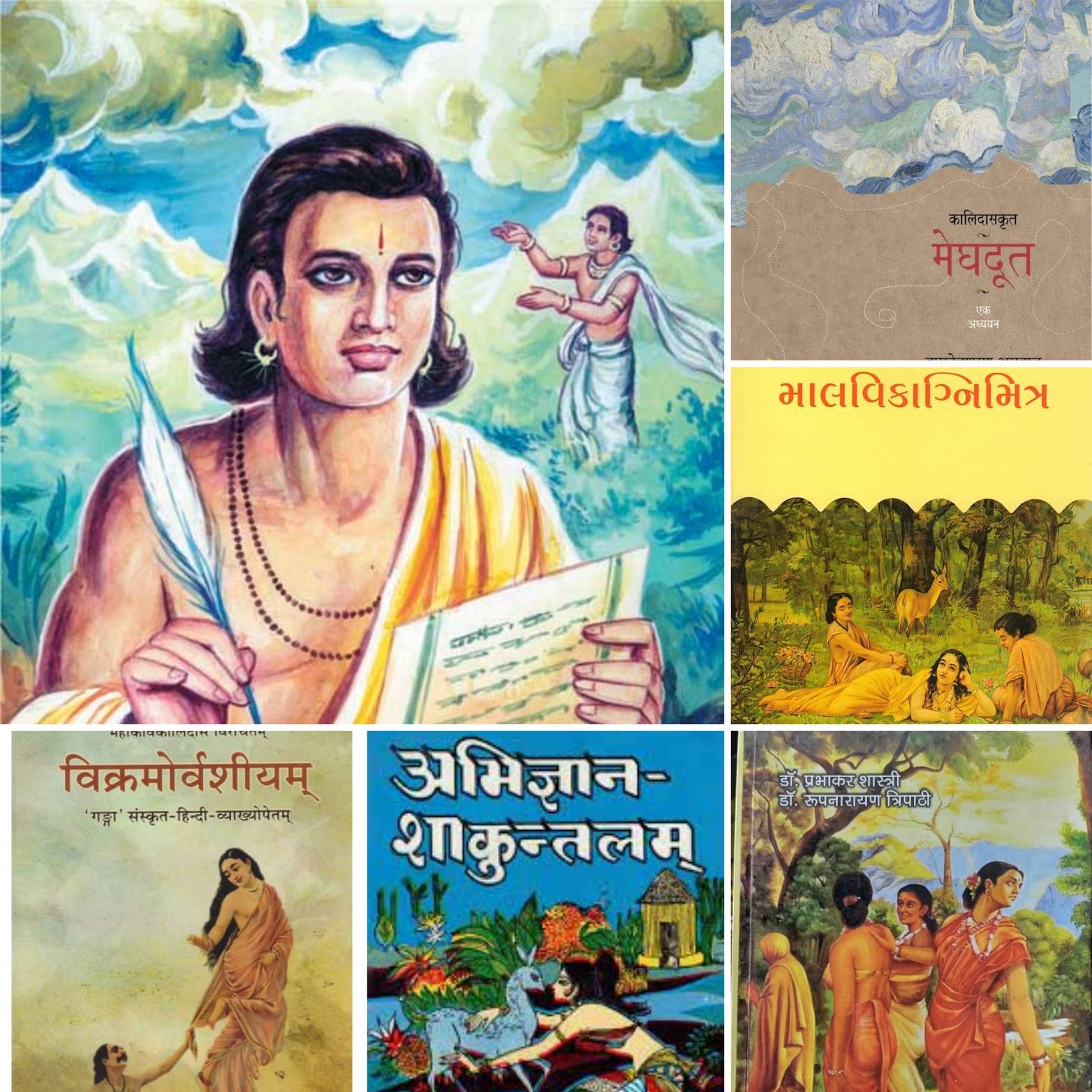

Kalidasa, the renowned poet-dramatist of ancient India, left a lasting mark on the association between literature and dance. His many works offer exquisite insights into the art of dance, aligning perfectly with the principles of the Natyashastra. This introduction unveils Kalidasa’s deep understanding of dance, weaving together the elaborate relationship between his literary brilliance and the world of dance.

Both kavya and natya literature comprises dramatic verse that lends itself easily to dance interpretation. The poet-dramatists like Kalidasa were extremely well-versed in understanding the principles of dance as codified in the Natyashastra and other texts. In fact, Kalidasa’s entire body of literary work is highly embellished by wonderful and correct references to and descriptions of music and dance. According to Shri G S Ghurye, “Outside Bharata’s Natyashastra, the earliest reference to dance showing technical knowledge and by implication giving other important information is that which occurs in Kalidasas’ ‘Malavikagnimitra’. Barring accounts in Natyashastra and the puranas, Kalidasa appears to be the earliest writer to make a pointed reference to the daily evening dance of Siva. In his ‘Meghadutam’, Siva requires an elephant’s ‘blood-dripping’ hide which he holds with two of his hands over his head while dancing. Siva’s dance with this peculiar equipment has been sculptured in South Indian temples from about the 7th century onwards. Kalidasa’s ‘Rutusamhara’ is a fine example of kavya literature (poetry-based in content) but his ‘Malavikagnimitra’, is an example of natya (drama-based content) literature. In another not very well-known work by Kalidasa, Vikramorvasiya, the celestial dancer, Urvashi performs and enacts the eight major rasas with aplomb. This work also reveals how well and in minute detail Kalidasa understood classical dance and music.

The most appropriate similes that he uses in his famous works, Meghadootam and Rutusamhara, not only establish his imaginative use of language but also his deep understanding of dance gestures and terminology. For instance, in Meghdootam, there are elaborate descriptions of dances performed by the Ujjain women and the grace of women dancing in Alakapuri. The sounds of thunder and impending rain that send the peacocks in a dance of frenzy. In his other work Raghuvamsa, Kalidasa moves beyond just the description of a human figure dancing, to eloquently comparing the grace of climbing creepers to the hands of a dancer as it moves in gesture, and the melodious humming of the bees as equivalent to accompanying music. In a truly extraordinary simile, Kalidasa even compares the movements of branches of a young mango tree to that of a bashful young dancer just starting to learn abhinaya! It is believed that when Kalidasa saw plants and leaves fluttering in the gentle breeze, it reminded him of a bunch of girls dancing together! Examples of such thinking are apparent in AbhigyanShakuntalam and Vikramorvasiyam.

In Abhijnanashakuntalam, Kalidasa’s seminal work, the poet’s stage directions are very meticulous. What is however most interesting is his creative adaptation of dance hastas and movements to express what is physically not possible to show on stage. In Indian Classical Dance, Dr. KapilaVatsyayan explains this as “In the Abhijnanashakuntal, at the very beginning we have Dushyanta entering the stage as if riding a chariot. We can easily infer that the movement of riding the chariot was depicted through angikabhinaya. Dushyanta is after the deer and the whole process is described with angikabhinaya. The deer is represented not by an actual deer but by a dancer wearing a deer mask, the movement possibly the harinapluta movement. The karana is derived from atikrantachari. A pair of katakamukha hands of the Natyashastra, are crossed at the wrists.

There are not just references to formal dance performances in the court or the temple, but several opportunities for social or folk dancing, the courtesan’s dance, and so on. It thus establishes a strong reference for Natyashastra’s detailed descriptions of various prevalent styles of dancing. The occasion of Raghu or Lord Rama’s birth in the poem-play, Raghuvamsa, is celebrated in the streets of Ayodhya by folk dancing, and in the havelis by joyous dances by courtesans. Such dancing is described as ‘mangalanritya’ and ‘pramodanritya’. It spreads joy all over the world and touches the shores of heaven itself!

The author-poet was also the perfect stage-craftsman, a sharp dramatist who knew the value of time and audience patience. But where the theme of dance is concerned, Malavikagnimitra is Kalidasa’s masterpiece. The story here is imaginary, situated in 150 BC in the court of King Pushyamitra, a patron of the performing arts. This allows for Kalidasa to introduce the formal auditorium (Prekshagraha) and rehearsal rooms into the script as the imaginary sets. The content itself is replete with several detailed technical references to the performance and its challenges to the dancer. This is obviously because the central female character, Malavika, is an accomplished dancer and her performance is the central focus of the poem-play. Hence there are several descriptions of the various items she selects as part of her repertory, the skill of the music accompanists – singers and instrumentalists, and above all, the electrifying beauty of her own performance. As a result, several supporting characters are also intimately connected to the practice of dance. There are two dance masters, Haradatta (patronized by the king) and Ganadasa (patronized by the queen). They are referred to as natyacharya, abhinayacharya and nartayita while their work is natya, abhinaya vidhya and Shilpa. The dancer is referred to as patra (as per Natyashastra and Sagitanarayana). Like most dance teachers, Haradatta and Ganadasa were accomplished dancers themselves, trained in a strong dance tradition and technically perfect. They understood well the principles and differences in theory (vidya or sastra) and praxis (prayoga). They were adept in the theoretical understanding of dance as well. In fact, it is Ganadasa who ascribes the tandava and lasya aspects of dance to the Ardhanarishwara form of Shiva. Ganadasa, the dance-master of Malavika informs us that Malavika was very quick of understanding and dexterous in practice of expressive movement (‘bhavikam’). We have to understand that the dance master explained to Malavika, the gestures, postures and movements which together, forming the configurations, could convey to the audience the notion and experience of a particular state of mind (‘bhava’). Malavika, on her part, immediately grasped them and not only reproduced without blemish the instruction in her performance but also improved on it in her manner of actually executing the configurations and creating the attendant emotional atmosphere. Later, Ganadasa says that he had just instructed Malavika on ‘panchangabhinaya’, representative gestures and postures of the five limbs. This is exactly the wording of BharataNatyashastra.”

In Kalidasa’s Malavikagnimitra there is a unique reference, the most valuable for the present purpose of the solo dance recital. Malavika’s performance is a perfectly executed classical solo dance number. Her execution of nritya and abhinaya is flawless, and as if the author’s evaluation is not enough, Kalidasa imaginatively places an objective spectator – parivrajika – in the audience to critically comment on the performance. Malavikagnimitra provides other important examples of space manipulation and zonal treatment of the stage, as also significant stage directions for ‘angikabhinaya’. While Malvika’s dance recital is the most finished and refined presentation of classical dance technique, it was distinctly different from the popular group dances of the time and was rather like contemporary dance performance in which the dancer is a solo performer depicting the emotions of various characters. With a combination of deft footwork, expressive hand and eye movements, mobile facial expressions, her dance was performed to the perfect accompaniment of song and tala. Kalidasa’s description in Malavikagnimitra of a lady standing with her left hand resting on her hip and the right hand hanging loosely by her side is reminiscent of the Dancing Girl figurine from the Mohenjo-Daro excavations.

He mentions that even while the dancer is motionless, she looks much more attractive than when she is dancing. Kalidasa’s poetic imagination allowed him a far more deeper understanding of movement and its expressive possibilities.

One must understand that during the time of Kalidasa, society had evolved significantly in the cultural domain, with great refinement of language, polished social behavior, and a highly developed taste in and understanding of drama, dance and music. Viewers and audiences were well-informed, academically incisive and rigorously critical. No author dared to deviate from what the Natyashastra had penned down and that learned tradition was followed meticulously.

In conclusion, Kalidasa’s works reveal his profound understanding of dance, effortlessly amalgamating literature and the art of movement. His detailed descriptions of dance, from classical solo performances to folk and courtesan dances, showcase his expertise in both kavya and natya literature. Kalidasa’s precise stage directions and creative adaptation of dance movements in his renowned work “Abhijnanashakuntalam” exemplify his mastery. His imaginative use of language and deep grasp of dance gestures and terminology are evident throughout his writings. Kalidasa’s legacy survives as a proof of the rich cultural heritage of ancient India, where literature and dance harmoniously converged, leaving an undeniable mark on the world of performing arts.