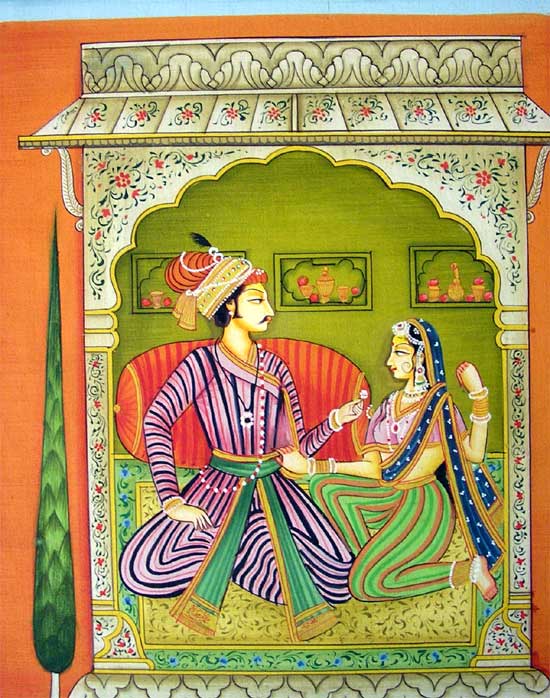

Bhanudatta is the most famous Sanskrit poet – certainly the most famous Sanskrit poet of early modern India. Bhanudatta was from Vidéha (today’s Northern Bihar), a member of the highly learned Máithili Brahmin community, and the son of a poet named Ganéshvara (or Ganapati). No other Sanskrit poet exercised anything remotely approaching Bhanudatta’s influence on the development of the Hindi literary tradition between 1600 and 1850, the “Epoch of High Style” (riti kal). Another indication of the importance of Bhanudatta’s work is the impact it made on the emergent painting traditions of early modern India. The “Bouquet of Rasa” was one of the best-loved poems in the sub-imperial realm of miniature painting that arose with the consolidation of Mughal rule at the end of the sixteenth century. The poem was illustrated in Mewar perhaps as early as the 1630’s, in the Deccan in the 1650’s, in Basholi between 1660 and 1690, in Chamba about 1690, in Nurpur in the 1710’s, and elsewhere.

It has various classifications of Nayikas. Bhanudatta, the author of Rasamanjari (which dates from the half of the fifteenth century) declares the superiority of the erotic rasa over the other aesthetic experiences and he states that this rasa is understandable only by the examination of the nayikas. There are about 384 types of Nayikas described in Rasamanjari.

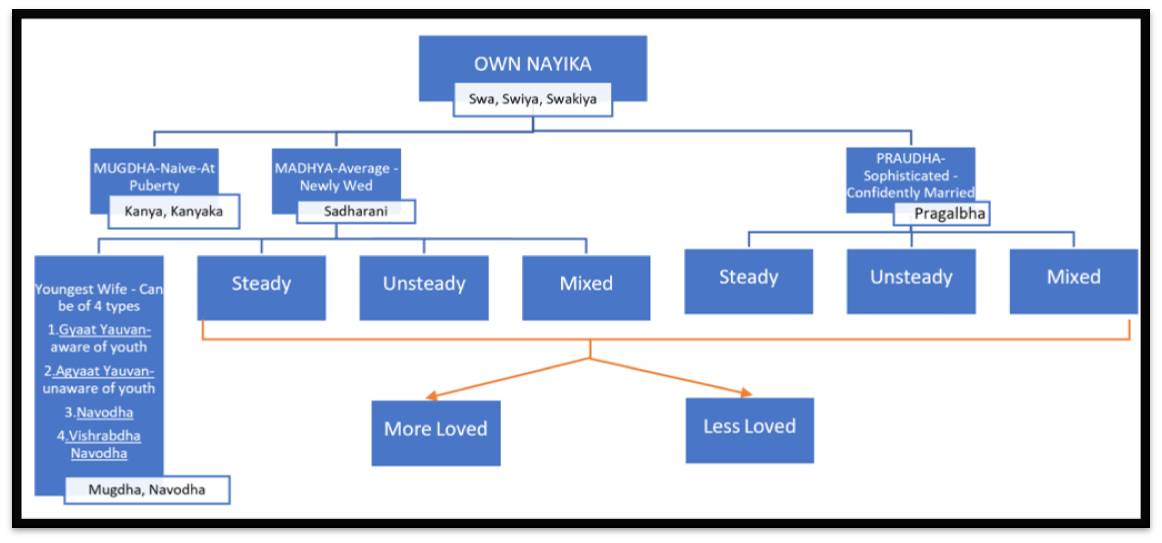

One’s own nayika ( Swa, Swiya or Swakiya): She is herself of three types:

- Mugdha: the naïve– The naïve is a girl who is just reaching puberty, and she may or may not understand its manifestations.

- Madhya: the average– The same naïve náyika is in due course a “newly married” woman, who is bashful and timid in her desire. A náyika is average if her desire and modesty are in balance. Because of her extreme compliance in lovemaking, the same woman is sometimes also classified as a very confident new bride.

- Praudha: the sophisticated or experienced– In due course, the average nayika becomes the “confident newly married” woman, who is more compliant. Her characteristic behavior is as follows- She enchants with the modesty of her actions, she is mild in her love-anger, and eager for new ornaments. The experienced náyika is skilled in all the arts of love- making, which takes place solely with her husband. She enjoys sexual intercourse, and she can lose all awareness in the bliss of lovemaking.

The average and the experienced náyikas each have three subtypes with respect to states of anger:

- Steady (Dhir),

- Unsteady (Adhir),

- Mixed (Dhiradhir) that is, both steady and unsteady.

The Madhya Dheer expresses her anger by dark hints.

The Madhya Adheer expresses her anger by sharp stabs.

The Madhya Dheeradheer, by words and tears.

The Proudha Dheer evinces a string indifference to the pleasure of her husband’s company.

The Proudha Adheer shows anger by threats and chastisement.

The Proudha Dheeradheer uses all the three methods.

These six types of angry women are again divisible into two subtypes, depending on whether the náyika is more loved or less loved- Jyestha (one who has found greater favour in the eyes of her husband), and Kanistha( one who stands only next in his estimate)

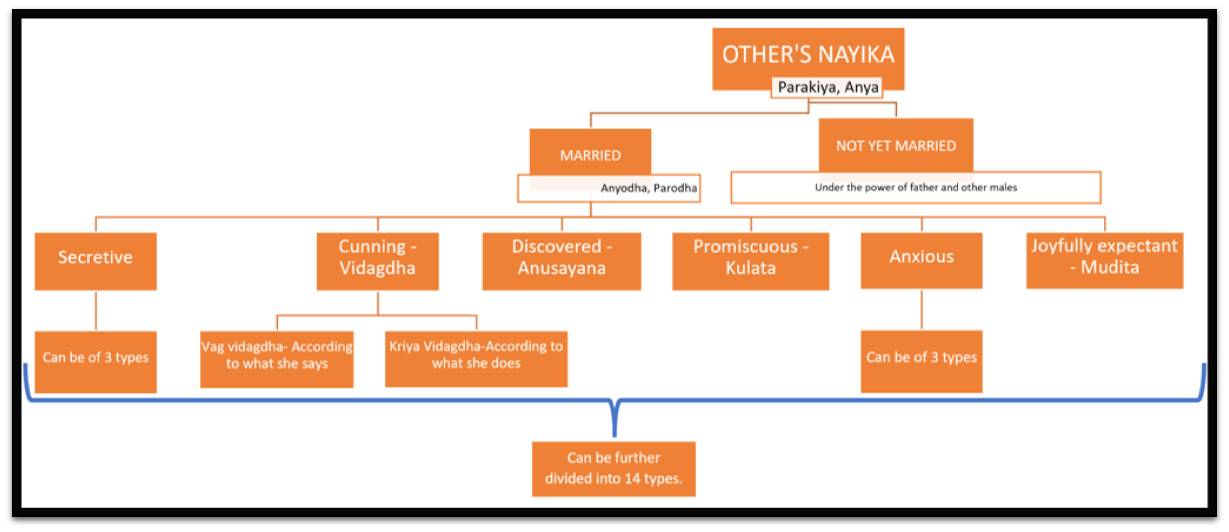

Other’s Nayika ( Parakiya, Anya): This náyika is another’s, but in love with another man, yet her love is kept hidden. This náyika is of two sorts-

- Anyodha, Parodha: She is married to another man.

- Not yet married: The latter is another’s insofar as she is under the power of her father and other males. The characteristic behavior of this náyika is total secretiveness.

Within the class of another’s náyika 6 subtypes are included:

- The secretive: Gupt-The secretive girl is of three sorts, according to whether she conceals an episode of sexual intercourse that has taken place, or one that is about to take place, or one that already has taken place and will again.

- The cunning- Vidagdhaa: She is of 2 types-

- Vaag vidagdhaa- according to what she says

- Kriya Vidagdhaa- according to what she does

- The discovered- Anushayaanaa

- The promiscuous- Kulataa

- The anxious- Lakshita: She is of 3 types-

- The one anxious over the disturbance to the normal meeting place.

- The one anxious over whether the meeting place will be available.

- The one anxious about inferring if her lover went to the meeting place when she wasn’t there.

- The joyfully expectant- Muditaa

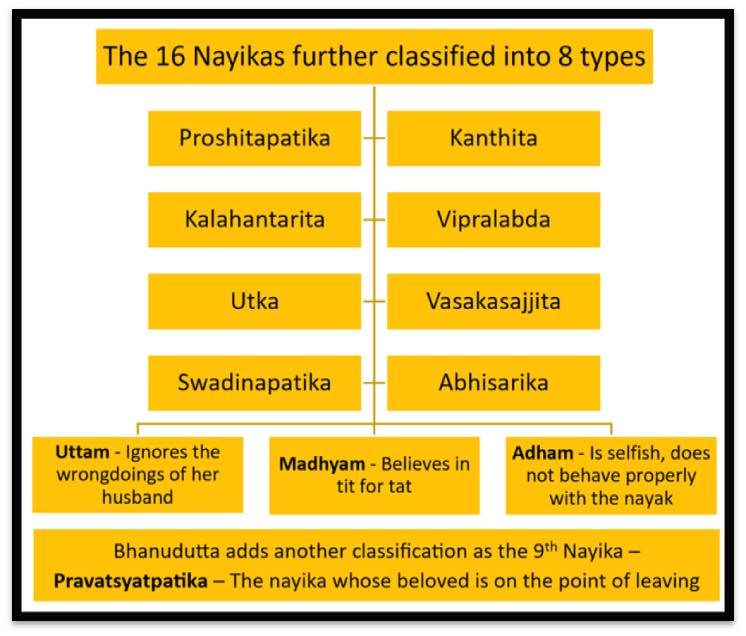

Each of the sixteen types of náyikas described so far can be further subdivided into eight sorts:

- The woman whose lover is away on travels. She pines for him and may go through all 10 stages of bereavement-(proshitapatika)

- The woman whose lover has cheated on her. He presents himself to her on daybreak with marks upon him of the previous night’s dalliance with her rival. Her words struggle her expression, she is sad and thoughtful, hot sighs reveal her anger and pain, silent contempt is her only reply. -(khandita)

- The woman separated from her lover by a quarrel. She is the one who has punished her lover too severely and repents keenly. She is confused in mind, penitent, heaves deep sighs. High excitement and raving mark her. -(kalahantarita)

- The jilted woman. She is the one who misses her lover at the place of assignment and is heavy of heart as a consequence. Despondence, hot sighs, excitement, moans, fear, blaming her friend, anxiety, tears, and faints mark her. -(vipralabda)

- The worried woman. She is the one who tries to explain the absence of her lover at the place of meeting. Dislike of everything in the shape of pleasure or enjoyment, excitement, yawns, stretching out limbs, false tears and pouring forth her sorrows to others are her characteristics. -(utkaa)

- She is the woman preparing for the occasion of her lover’s reception. She lives over the future in anticipation. She is in a mood to banter her friend. She questions her friend whom she has sent to her lover. She bestirs herself with gathering the materials for the reception. Ever and anon, she casts her looks along the road he must take. -(vasakasajjita)

- She is the woman whose lover is under her thumb. She is ever assured of the love and service of her husband. She delights in pleasant walks in the woods with other amusements. She is in high spirits and is proud of her peculiar good fortune and is never disappointed in her expectations. -(swadinapatika)

- The woman who goes on a secret rendezvous or makes her lover come to her. Her dress and ornaments are perfectly adapted to circumstances. Doubts, skill, resourcefulness, deceit and audacity mark her. This is true in the case of a Parakeeya whose aim is not to be found out. -(Abhisarika)

This makes 128 types. All these can be further distinguished as excellent (Uttam), average (Madhyam), and low (Adham), which thus gives 384 types.

- Uttama Nayika– She ignores the wrongdoings of her husband. She returns good for evil in the case of her lover.

- Madhyam Nayika– Believes in tit for tat and responds with similar behaviour towards her husband. She returns like for like.

- Adham Nayika– She is selfish and does not behave properly with the Nayaka. Also called Chandi when her unreasonable anger bursts forth. She returns evil for good in her lover. Her behaviour is correspondingly low.

All these are again divided into the Divya(celestial), the Manaba(human) and the Misra (semi-divine or mixed). Indrani. Malati and Sita are the respective examples.

Bhanudatta explains the objective relation between the nayika and the man. So, we have the subject’s own partner- (Swa, Swiya, Swakiya); ‘the other man’s partner’ (parakiya, anya); the unmarried girl (kanya, kanyaka) ; and the adulteress (anyodha, parodha), the common woman ( sadharani), the courtesan( samanya). The swiya is always faithful, fair, honest and she considers her husband as a God. In particular, the youngest wife (mugdha, navodha) is timid in love and naive in her behaviour; she is in full possession of the maybe preferred quality of the women, the bashfulness (lajja) is very seductive for the man, who takes great pleasure in his role as a teacher in the erotic science. The nayika of ripe age (praudhaa, pragalbhaa) acquires on the contrary self-consciousness and arrogance, in other words dhiratvam: she knows well the erotic art, and this is very agreeable for her partner, but also becomes most quarrelsome, possessive in love and jealousy, and frequently she is insolent to the unfaithful husband. The parakiya is described as impudent, always resolute and ready for crossing every obstacle in order to conquer the lover and make love with him.

Bhanudatta agrees to the traditional “relationship’s qualifications” by showing a very great originality in the study of the lyrical literature. He already starts to trace some new subdivisions of the nayikàs:

1. The youngest wife (mugdha or navodha), is of four types according to her degree of self-consciousness about the love-

- Aware of youth- “Gyaat Yauvan”

- Unaware of youth- “Agyaat Yauvan”

- Navodha

- Vishrabdha Navodha

2. The women of ripe age, who are in possession of the traditional quality of the “arrogance”, are further sub divided according to their lack of hesitation in front of the partner and above all according to their knowledge of the erotic art.

The author makes clear, therefore, that the degree or dhiratvam must be estimated in relation to the sexual experience and that a satisfying sexual life is the true touchstone of the happiness of a couple, both conjugal and adulterine. He also maintains expressly that the arrogance; is present also in the unmarried girl and mostly in the adulteress. ln effect, the adulteress is explicitly and open-mindedly defined not as a dishonest woman but a woman who has fallen in love with a man who is not her husband. The parakiya is in her turn subdivided in fourteen new types. These new subdivisions emphasise not only the canonical qualities of an asati woman, namely the cunning and the one free from prejudice, but above all her immense disposability to love and to suffer in the love’s affairs – exactly as a sviya. Sometimes, in the description of a type of the adulteress, Bhanudatta cites as an example Radha and a moment, happy or unhappy, of her love’s story with Krishna.

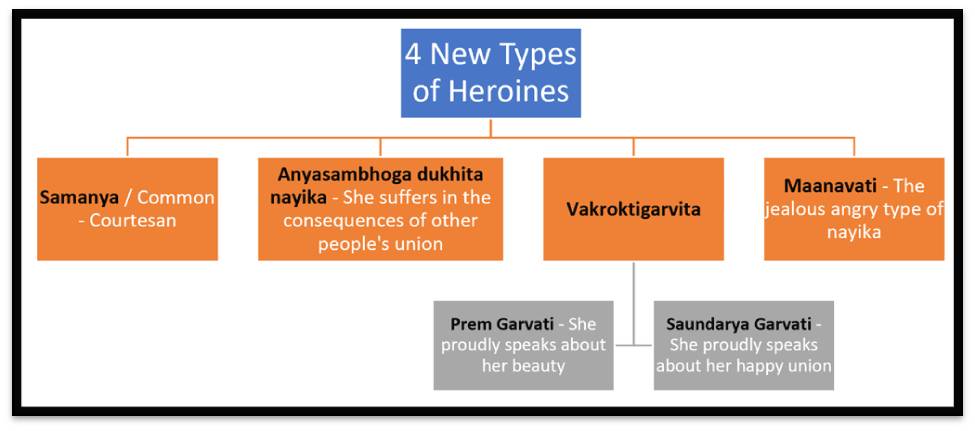

The text offers the illustration of other four new types of “heroines”-

- Samanya- Common – Her love towards men in general is measured by the length of their purse.

- Anyasambhogaduhkhita– who suffers in consequence of the other people’s union.

- Vakroktigarvita– the nayika who is proud and speaks using indirect speech (about her beauty- “Saundarya garvati” or her happy union- “Prem garvati”)

- Maanavati– the nayika who is jealous and angry. She can be of 3 types-

- Laghu– the one who is pacified without difficulty. She gets angry at the very sight of another woman. She is won over by seeking means to divert her attention and curiosity.

- Madhyama– the one whom it is difficult to bring around. She gets furious at the very mention of the name of her rival by her lover. She is brought back by him adroitly defending himself or, if necessary, by hard oaths.

- Guru– the one who is very hard to tackle. She is implacable because she had caught her lover red-handed. She is pacified by presents of dresses and ornaments and, as a last resort, by falling at her feet.

All these new categories, portrayed in this treatise for the first time, are extremely thought-provoking for three reasons:

First, the author demarcates clearly, unlike the most ancient advocates, the associations among the women, which are always undetermined between the friendship (we must think to the acknowledged characters of the bosom-friend”- sakhi, and of the love’s messenger- (Duti) and the competitiveness (we must think to the repeated subject of jealousy); on the other hand, the verse itself shows that when a nayika is joyful, often other women are suffering in front to the separation of the common-lover or of the common-husband – a womanly and accurate visualisation of the polygamy, very different from that, for example, of the majority of the dramas with their sometimes forced or uncaring final bond among the beloved nayika, the empress and the mistress.

Second, Bhanudatta, as a matter of fact, illustrates by means of these categories the two essential circumstances of the love’s stories, the union and the separation, which the other debaters have attempted to prove in the chapters of their treatises devoted to the rasa of love – it is true especially for the jealousy, maybe the most frequent motive of vipralambha. In other words, the author makes clear that the love’s situations are in fact the various emotional states of the “heroine”.

Third, Bhanudatta stresses again that these types of “heroines” are proper to all the nayikas portrayed in the light of the “relationship’s qualifications”, the “wife”, the “adulteress” and the courtesan. Therefore, the author doesn’t reject the ancient tradition but explores again and goes deep into it. And, unlike his precursors, he connects the traits of every nayika, showing that all the “heroines” are subject to all and to the same love’s sentiments.

Bhànudatta also underscores that all the eight “circumstantial qualifications” can set in motion the ten phases of the love:

- The yearning for the meeting between the parties

- Deep thought about the effecting of a meeting and its happy consequences

- Calling up memories of the words and acts of one another

- Holding forth the excellences of one another

- Utter distaste towards everything, induced by her burning love.

- Moans, bewailing and expressions of grief, sorrow and bereavement

- Madness displayed in words or acts due to pain of heart and disappointed hopes.

- Illness of body and mind due to the pangs of barren emotions and a wasted life

- Utter paralysis of body and soul with but the breath of life to indicate what she suffers from separation.

- The last stage is death, is not treated of as it is inauspicious.

He confirms, in other words, that the so-called sickness of love, (kaamavyaadhi) can drain all the nayikas (from the naive new-married girl to the clever adulteress), and that the experience of desire is very frequently, for the nayika, an unfortunate experience. Infidelities, rejection, apathy by the beloved partner are always probable, maybe possible.

The matter is perfectly established by Bhànudatta by way of a new, ninth “circumstantial qualification”, which can be applied, as the others, to all the nayikas: the “pravatsyatpatika” or “the woman whose beloved is on the point of leaving” – a paradoxical circumstance in which the union still exists but the separation is impending —given that her lover has decided to leave for another country and might depart at any moment. That is to say, this type cannot be included in the category of “the woman whose lover is away on travels” or the “jilted woman” or the “worried woman,” since her lover is still present. She cannot be included in the category of “the woman who is separated from her lover by a quarrel,” since there has been no quarrel, and she has not spurned her lover. Nor can she be included in the category of the “angry” náyika, since her lover has not appeared with telltale marks of lovemaking with another woman, and accordingly she does not show any anger with him but on the contrary shows a predilection for sarcasm, anxious glances, and so on. She cannot be included in the category of “the woman preparing for the occasion,” for there is no restriction in this case as to occasion, and she shows, not the preparing of her bedchamber, but rather despair, and so on. She cannot be included in the category of “the woman whose lover is under her thumb,” because here their relationship will be interrupted the very next moment. This new type of “heroine” fully shows that the most typical situation of every woman, in all the love’s stories, is that of the uncertainty and of the waiting: the man, and the man’s wills, draws the woman’s destiny. The sacred Tradition is newly reversed in front to the fatal laws of the love: the life of the women is traced by that frequently frivolous Deity who is the man.

This type of the pravatsyatpatika makes clear four matters. First, all the nayikas are slaves of the masculine inconstancy in love; second, the possession of the beloved man is always uncertain; third, all the nàyikas are at the mercy of the ten stages of the love, because also if the first stage, the longing (abhilasa), is apparently satisfied in the union, the separation can suddenly and unexpectedly happen, throwing the woman on the other nine, until the death; fourth, the unpredictable nature of the love is, as a matter of fact, the unpredictable nature of the man. Bhànudatta doesn’t explain by any means why the lover of the pravatsyatpatika is on the point of leaving. This is his will. She is a paradigmatical type: the troubles of this nayika, described almost always in the realistic and impressionistic form typical of the muktayas, are not obliterated by the happy end. They are not annihilated by a tragic end. So, the real life, with this dramatic uncertainty, breaks into the art with its entire burden.

At the end of the Rasamanjari, Bhanudatta illustrates very briefly the sringara rasa in its two classical categories of the sambhoga(love in union, sexual fulfilment) and of the vipralambha(love in separation): obviously, the ten stages of the love are applied to the second. But, at this point, the reader has well understood the message of the author: the rasa of the love, the most important aesthetic experience, is correctly intelligible only by the description and by the study of the different types of the nayikas and it exists only by the presence of them. The nayika, on her part, meets the happiness only in a happy relationship with her beloved, either her husband or a lover: her traditional roles of mother and of pious housekeeper are obliterated both in the rhetorical treatises and in the lyrical literature. Therefore, the love is the aim of all the women, the only beatitude, the only Heaven. But it is clear also that very frequently love means sufferance: a sufferance that the nayika faces with heroism until the boundary of the death.

Since sringara rasa requires a description of both partners, the náyaka, too, has been described.

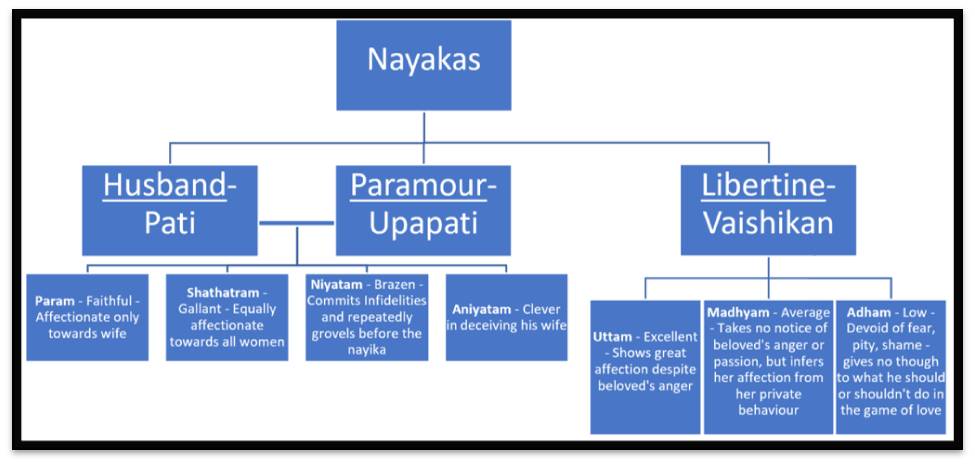

There are 3 kinds of Náyakas:

- Husband

- Paramour

- Libertine

A. Husband: Pati-There are 4 types of husbands:

1.Faithful (Anukula): A husband is faithful if he is constant affection toward his wife while constant in his lack of interest in the wives of other men.

2.Gallant (Dakshina): He is gallant when he is naturally and equally affectionate toward all women.

3.Brazen (Drishta): He is brazen when, although not hesitating to commit repeated infidelities, despite being warned against future misconduct, he repeatedly ends up groveling before the nayika as often as he is guilty.

4.Deceptive (Sata): He is deceptive if he is clever in deceiving his mistress. The love-angry and the clever are classed under the deceiving nayaka. He is hollow-hearted, crafty and ever treacherous to his love.

B. Paramour- Upapati: A man who causes a woman to forsake her virtue is a paramour. The paramour is also subdivided into the same 4 types as the husband. He is the secret lover who has fallen from the straight path of virtue.

C. Libertine- Vaishikan: A libertine is a man who has a great taste for affairs with courtesans. He spends his days in the homes of public women.

Libertines are classified as:

- Excellent(uttam): The libertine who shows great indulgence despite the beloved’s intense anger is termed excellent. He tries to pacify the outbursts of his lover.

- Average(madhyam): The libertine who takes no notice of his beloved’s anger or passion but infers her affection from her private behavior, actions and movements is termed average.

- Low(adham): The libertine who is devoid of shame, pity and fear and gives no thought to what he should or should not do in the game of love is called low.

The husband, the paramour, and the libertine can each be absent náyakas, giving three more types.

The Pati, Upapathi and Vaishikan are marked by their stay at home or absence abroad.

The stupid and dull-witted hero is simply the parody of the Nayaka.

The Peethamarda is one who is skilful in placating the angry woman.

The Vita is a past-master in the arts of love.

The Chetaka is proficient in bringing about meetings and assignments.

The Vidhushaka is the clown, the jester, and the harlequin who amuses others by his ludicrous speech, acts and movements.

Now, one should not suppose that the náyaka has the same subclassifications as the náyika. An essential distinction lies in the fact that the náyika’s different classifications derive from her different temporary states, whereas the náyaka’s derive from his inherent character, and there are only four such sorts of character: the faithful, the gallant, the brazen, and the deceptive.

In conclusion, Bhanudatta’s “Rasamanjari” stands as a remarkable and influential work in Sanskrit literature, serving as a foundation in shaping not only the literary traditions of its time but also the world of art, particularly miniature painting. Bhanudatta’s meticulous classification and investigation of the various types of nayikas and nayakas reveal a deep understanding of human emotions, relationships, and the complexities of love.

Through his work, Bhanudatta emphasizes the central role of love in human experience and illustrates the intricate dance of emotions within romantic relationships. His portrayal of the nayikas and nayakas highlights the universality of love’s trials and tribulations, from the naive new bride to the cunning adulteress, all subject to the unpredictable nature of the human heart.

Moreover, Bhanudatta’s work challenges traditional roles and expectations of women, presenting them as complex individuals driven by desire, passion, and the pursuit of happiness. The dynamic chemistry of characters and emotions showcased in “Rasamanjari” serves as a testament to the enduring power and relevance of love in the human experience.