“No artist is ahead of his time. He is his time. It’s just that the others are behind his time.”

-Martha Graham

Music and dance are a medium not as rigid as drama, theatre or movies and hence can survive

amongst varieties of audiences and instil certain emotions and sentiments in them as the

language barrier does not hold a tight control over them. The visual appeal and display

through all four abhinayas- Angika, Vachika, Aharya and Sattvika help create entire scenes

weaving through time, history, relationships etc as they are accompanied with movement,

semantics, and melody. This is achieved in dance through thoughtful compositions that are

created keeping in mind the mood of characters, the choice of raga for that mood, the rhythm

that would align itself perfectly with the said sentiment and the right choice of words- either

self-made or taken from the granthas, scriptures and other such texts. In the history of

Bharatanatyam, many Gurus effectively created many new margams, bearing in mind the

changing needs, demands, acceptability and performance diktats that evolved in the dance

presentations over a period of time.

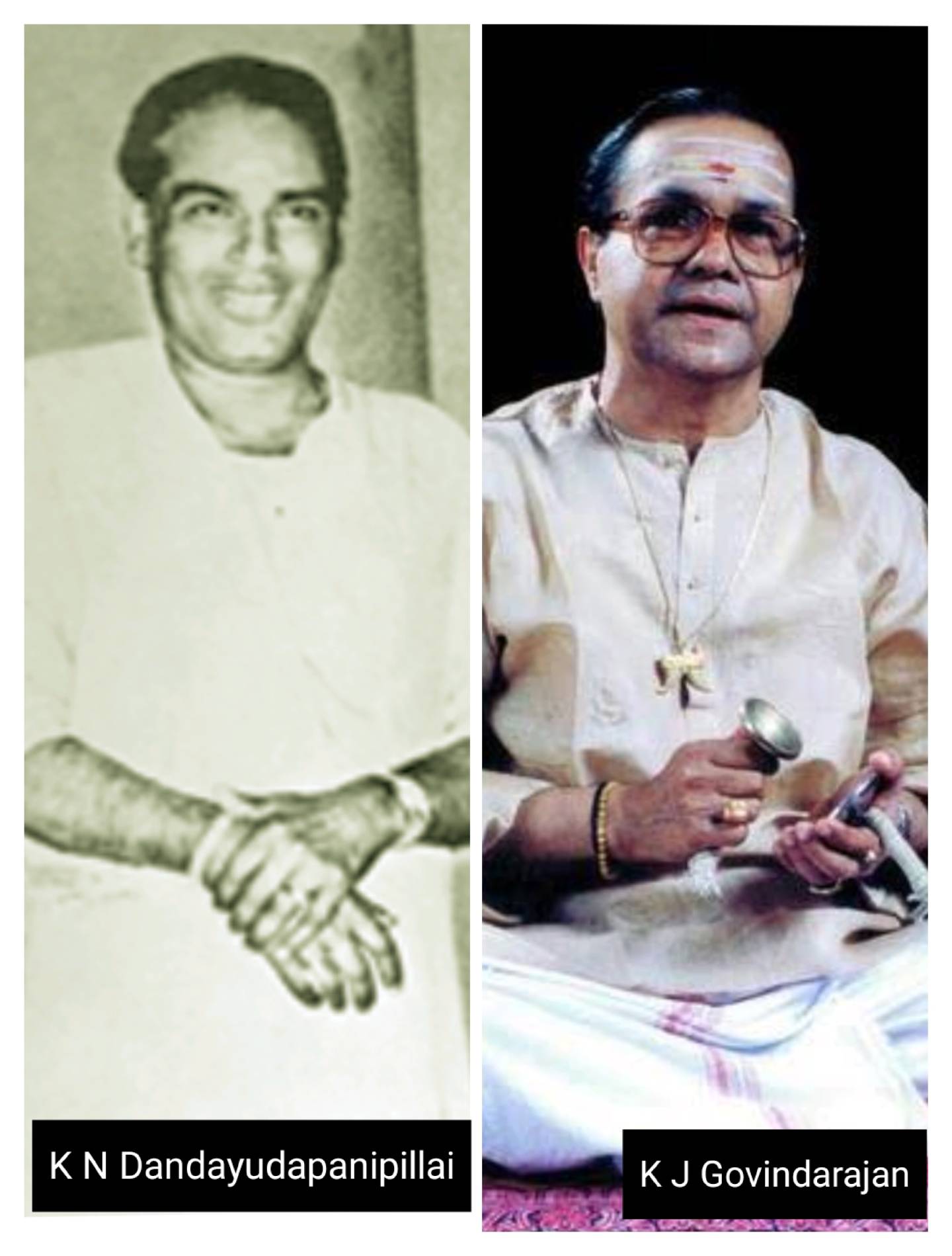

Two names stand out distinctly – Padmashree Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai and Guru K J

Govindarajan. I not only compare Guru K J Govindarajan with Guru K N

Dandayudapanipillai out of a personal connection, i.e., receiving training directly from the

niece and disciple of the latter, but also because the compositions of both Gurus inspire me to

choreograph and perform, despite my not being fluent in the language of their choice (Tamil).

Such is the power or magnetism of their melodies and rhythms that they rouse and stimulate

the creativity of dancers and teachers to desire to create something artistic in terms of

emotional complexity as well as musical tempos.

As I investigated deeper into the lives of Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai and Guru K J

Govindarajan, a striking pattern began to emerge – not just in their artistic output, but in the

very fabric of their personal journeys. It was as if destiny had woven parallel threads through

their lives, binding them with uncanny similarities. Both hailed from culturally rich families

that nurtured their artistic inclinations from a young age. Their educational paths, though

distinct in detail, were rooted in a deep reverence for classical tradition and a hunger to

innovate within it. What truly captivated me was their shared intention: not merely to

perform, but to elevate Bharatanatyam into a vessel of storytelling that could transcend time,

language, and geography.

Their passion was not performative – it was devotional. Every composition, every rhythmic

phrase, every choreographic choice seemed to echo a commitment to authenticity and

emotional truth. And in their creations, one finds not just technique, but soul. Despite the

generational gap, their artistic philosophies seem to converse with one another, as if they

were kindred spirits separated by time but united by purpose. It is this resonance that

continues to inspire dancers like me – not just to replicate, but to reimagine, to feel, and to

create.

Below is a step-by-step look into the resemblance of their lives and how they finally turned

from performers to gurus to choreographers and finally composers:

1.Belonging traditionally to a lineage of traditional artistes:

Both Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai and Guru K J Govindarajan hailed from the Isai Vellalar

community – a lineage deeply rooted in the preservation and propagation of South Indian

classical arts. The term Isai Vellalar itself translates to “cultivators of music,” and that’s

precisely what this community has done for centuries: nurtured, refined, and passed down the

rich traditions of Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam with unwavering devotion.

Historically, Isai Vellalars were custodians of temple arts, serving as musicians, dancers, and

teachers in royal courts and sacred spaces. Their homes were often vibrant with rhythm and

melody, where art wasn’t just practiced – it was lived. This cultural inheritance gave both

Gurus not only technical mastery but also an intuitive understanding of the emotional and

spiritual dimensions of performance. It’s no surprise, then, that their compositions carry a

depth that resonates across generations and transcends linguistic boundaries.

To belong to the Isai Vellalar tradition is to carry the pulse of centuries in one’s veins. And

both Gurus, through their innovations and teachings, honoured that legacy while also

expanding its horizons – making Bharatanatyam not just a classical form, but a living,

breathing language of human expression.

Born in 1921, Guru KN Dandayudapanipillai belonged to an outstanding musical descent of

conventional nagaswaram players of Karaikal. His father, Karaikkal Natesa Pillai, was a

versatile vocalist. His grandfather was Nagaswaram Vidwan Ayyasami Pillai. The illustrious

Rajaratnam Pillai was the brother of his first wife Subhadra. His grandfather’s brother,

Ramakrishna Pillai, a talented musician and nattuvanaar was also a well-known

Bharatanatyam Vidwan. Guru Dandayudapani Pillai was also a relative of Pandanallur

Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai. Guruji’s brother-in-law, Tiruvengada Subramanya Pillai and

Uncle Sangeet Kalanidhi P. S. Veerusami Pillai and many more made Carnatic music richer

by their contributions.

In 1934, late Guru K J Govindarajan was born in Kiranur in Tanjavur to a family of

traditional nattuvanars, who played in the temples for dancers. His great grandfather,

Bharatha, was an established nattuvanar who lived in Marakanam, a coastal town of Tamil

Nadu, located about a hundred and twenty kms south of Chennai. His name is still engraved

in the Temple Stone of Marakanam. His Grandmother, Guru Kalyani Amma, was a versatile

Carnatic vocalist. She later shifted to Kiranur, in the Tanjore District. His Mother, Kiranur

Smt Jayalakshmi Amma was the First lady flutist of the Carnatic style.

These rich ancestral legacies reveal that both Gurus were not just born into music – they were

sculpted by it. Their lineage was a living archive of artistry, and through their own

contributions, they became brilliant links in an unbroken chain of cultural wisdom.

2.Training in Vocal Music, Nattuvangam and Dance:

Guru Dandayudapanipillai learnt music from his father, Natesa Pillai, and later from his

grandfather, Ramakrishna Pillai, who also trained Dandayudapani in the art of

Bharatanatyam. One of his elder siblings, Rukmini was an excellent vocalist, and he started

giving vocal performances with her from a very young age. He got advanced training in

vocal music from Tiger Varadachariar. His grandfather Ayyasami Pillai also trained him in

the field of art. While at Kalakshetra, he used to give vocal support for Rukmini Devi’s

performances alongwith Chokkalingam Pillai on the nattuvangam. Since he was in Chennai,

Dandayudapani approached Nattuvanar Katumanarkoil for satiating his passion for learning

nattuvangam at this stage. Guru Dandayudapanipillai learnt the art of nattuvangam as he had

a deep passion for it. He took training for nattuvangam from Kattumanarkoil

Muthukumarappa Pillai.

Guru Govindarajan began his training in vocal music at the age of ten. He used to live in the

home of his guru and performed ‘seva’ in lieu of the monthly fees. He learnt from Gurus

Vidwan Narayanswami of Thirumaigyanam and Issaimani T.V. Namasivayam of Thiruvarur.

He gave his first solo vocal recital in a temple when he was just fifteen years old, in 1950. A

few years later, in the 1950’s, he also learnt to sing the Tiruaruptas of Ramalingaswami in the

established construct under the tutelage of Kiranoor Arutjyoti Vallalar at the Chidambaram

temple. Under the guidance of Asthana Ramalingaswamigal Vallar devotee, Kripasamudra

Swamigal, he trained to render the Tiruaruptas in the traditional format. For almost ten years,

he sang in all the “Samarsas sanmarga Sangam” units in Tamil Nadu. Govindarajan ji, over

and above his music training, started training in Bharatanatyam from the Pichaiya Pillai

Vidyalaya, Tanjore. Although Pichaiya was no more when Guru Govindarajan joined his

dance school, T. M. Arunachalam trained Guru Govindarajan in the Pichaiya bani. He

accompanied dance programmes at the Pichaiya School till 1959. As a young boy, he

acquainted himself with music, mythologies, and stories, learning the arts from the Pichayya

Pillai School. Later he learnt dance and nattuvangam under the guidance of Sikkil

Ramaswamy Pillai. It was a completely oral tradition, and he learnt it merely by

accompanying it.

Their journeys in vocal music, dance, and nattuvangam were not merely paths of training –

they were immersive pilgrimages into the soul of tradition. Through rigorous discipline,

heartfelt devotion, and the wisdom of legendary mentors, both Gurus absorbed the essence of

Bharatanatyam and Carnatic music, shaping themselves into torchbearers of a legacy that

continues to inspire and illuminate the artistic world.

3. The move away from their birthplace towards the pursuit of livelihood:

Having lost their fathers at an early age, both gurus, Dandayudapanipillai as well as

Govindarajan, moved out of their small respective villages in search of new horizons,

opportunities and the pursuit of their artistic endeavours. This move was also accelerated due

to the financial responsibilities upon their shoulders to support their families.

Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai, as a boy of 17, moved to Madras seeking livelihood as a

singer. He joined Kalakshetra as a member of the orchestra and assisted the renowned

Pandanallur Chokkalingam Pillai, who trained the students in Bharatanatyam.

Guru K J Govindarajan moved to Delhi in 1960, as an apprentice to Sikkil Ramaswamy

Pillai. One of the original institutions for classical arts to be established in the capital then,

was the Triveni Kala Sangam where with his formidable repertoire of classical compositions,

Guru Govindarajan started teaching music and afterward dance as well.

Their early journeys from Karaikal and Kiranur to the cultural epicentres of Madras and

Delhi were not just physical relocations – they were acts of resilience and artistic calling.

With the weight of familial responsibility and the fire of creative ambition, both Gurus carved

paths that would not only sustain their own lives but enrich the lives of countless students and

connoisseurs. Their transitions marked the beginning of legacies that continue to shape the

landscape of Bharatanatyam and Carnatic music across generations and geographies.

4. Founding Their Own Dance Institutions:

Empowered by rigorous training in vocal music, Bharatanatyam, and nattuvangam, both

Gurus went on to establish their own centres of artistic excellence. Guru K N

Dandayudapanipillai founded Natyakalalayam in Madras – a vibrant institution that became a

crucible for nurturing classical dancers and preserving the Pandanallur style with precision

and grace. Guru K J Govindarajan, carrying his formidable repertoire to the northern capital,

established Bharatanatya Niketan in New Delhi. His school became a cultural bridge,

introducing the nuanced aesthetics of Bharatanatyam to a new generation of students in North

India, and expanding the reach of the art form beyond its traditional geographic boundaries.

5. Training and Accompanying Renowned Dancers:

Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai collaborated with and trained some of the most iconic figures

in Indian classical dance. He consistently worked with legendary performers such as Yamini

Krishnamurthi and Padma Subramaniam and mentored a wide array of celebrated dancers

including Hema Rajagopalan, Sri Vidya – daughter of the renowned vocalist M. L. Vasantha

Kumari – Vyjayanthimala Bali, Jayalakshmi Alva, Jayalalitha, Kaushalya, Waheeda Rehman,

Asha Parekh, Rajasulochna, Chandrakanta, Manjula, Lata, Urmila Satyanarayan, and Usha

Srinivasan, among many others.

According to musicologist Dr. B.M. Sundaram, Guru Dandayudapanipillai was the only

Natyaacharya to participate in an English-language film, The River (1951), directed by Jean

Renoir. He contributed as both composer (of lyrics and music) and singer. A rare dance

clipping from the film features Radha Burnier performing, with Guru Dandayudapanipillai

providing nattuvangam. At the time, he was a senior guru and staff member at Kalakshetra,

where he played a pivotal role in shaping the institution’s artistic ethos.(Indian dance scene /

"The River" 1951 (youtube.com))

Guru K J Govindarajan also had an illustrious career accompanying and training eminent

dancers. He conducted recitals for Indrani Rehman and collaborated with M.K. Saroja,

Yamini Krishnamurthy, Raja Radha Reddy, Kanaka Srinivasan, and Sonal Mansingh,

traveling extensively across India to support their performances. Later, in New Delhi, he

trained a generation of acclaimed dancers including Swapna Sundari, Kiran Segal, Uma

Balasubramaniam, Jamuna Krishnan, Radha Marar, Rasika Khanna, Deepa Venkatraman,

Kodhai Narayanan, Sobhana Radhakrishnan, Nitya Krishnaswamy, Marie Louis Fischer,

Jalaja Kumar, Sindhu Mishra, Rama Krishnamurthy, Anne Marie Gaston, Rajika Puri, Kavita

(Shridharani’s daughter) Jaishankar Menon, Manish Chawla, Jai Govinda, Anand, Jayashree

Balasubramaniam, S. B. Pillai, Vani Rajmohan, Marie Elangovan, Lucia Meloni, Sudha

Gopalan, Ragini Krishnan, Rohini Krishnan, and Kamalini Dutt, as documented in various

newspaper articles.

A notable archival video captures Guru Govindarajan accompanying Padmashree M.K.

Saroja on vocals and nattuvangam during her performance in Switzerland in 1979. The tour

was organized by the legendary dancer Ram Gopal, who played a key role in introducing

Indian classical dance to international audiences. (Guru M. K. Saroja's performances and

award ceremonies (youtube.com))

6.Both gurus were expert ‘Vaggeyakaras’:

Composing for dance is a far more arduous task than creating a music piece for a concert.

Hence, a vaggeyakara must possess many qualities as laid down by the scholars. He should

have a sound knowledge of grammar, prosody, diction, and poetics. He should be well versed

in emotions and sentiments (rasa and bhava). He should have the capacity to understand

different languages. He must be an expert in nritta, gita, and vadya; should have a pleasing

voice; command over tala and layam; possess the ability to sing well; have the skill to unravel

a theme or create a new theme and the capability for elaborating ragas in multiple ways.

Additionally, he must know the technical aspects of dance also, so that the music befits the

mood, movement and abhinaya of the dance. He must understand the nonverbal restrictions

of his ideas and carefully select words that can be interpreted into mudras. In keeping with

these preconditions, such a person might also be termed as a ‘Nritya Vaggeyakara’.

Both the gurus not only penned down the lyrics of their songs but also tastefully tuned them

to befitting ragas. This places them in the category of ‘Vaggeyakkaras’, a term used in

Carnatic music for a person who is the lyricist as well as the composer of the song. Like

dancers and singers, dance-music composers occupy an important rank in the success of a

presentation.

Guru Dandayudapanipillai composed both the Dhaatu (word) and Maatu (music). Hence, he

is also considered an Uttama (true) Vaageyakara, i.e., composer of the ‘Vaak’- word and the

‘Geya’-musical process. Most composers of the past composed kirthanams, padams and

varnams in Telugu. He composed original jatis, Varnams, jatiswaramas, Padams and tillanas

in Tamil. He composed several Dance-ballets, scripted some, set the music for them and

choreographed some which were performed onstage by leading dancers and film stars. He

also made a breakthrough in Hollywood composing music and dance for the movie “The

River”. He even sang a song in the film.

Guru Govindarajan was also a very talented Vaggeyakara who created many compositions to

add to the Bharatanatyam margam. He wrote in Tamil, which was the primary and only

language he knew before he came to Delhi. He created Pushpanjalis, Kauthuvams, Varnams,

Jatiswaramas, Padams, Keerthanams and Tillanas. He also created many dance dramas.

7.Published books on various original compositions of different items of the Margam:

Guru Dandayudapanipillai composed over 40 items for the margam including numerous

jatiswarams, padavarnams, padams, tillanas and many dance dramas. He composed 9

jatiswarams, 9 padams, 9 varnams, 13 Tillanas and 10 dance dramas- Shree Krishna

Tulabaaram, Chitrambalaa Kurravanji, Silapaddikaram, Sivagamiyin Sabatam, Paadmavati

Srinivasa Kalyaanam, Thriruvidayaadal Puranam, Meenakshi Kalyaanam, Kaviri Tanta

Kalaiselvi being some of the prominent ones. His Navaragamalika Varnam in Adi Talam

dedicated to Lord Shiva is one of his most famous varnams. His book of compositions is

called “Aadalisai Amudam” which contains his jatiswarams, padams, varnams, tillanas and

jatis.

In his magnificent career of 34 years, Guru Govindarajan composed over 50 items for the

margam along with many dance dramas. His Varnam set to Raga Kambhodi called “Nee Poyi

Solluvan” remains a favourite amongst his students. He composed many dance pieces

including two Pushpanjalis, an Ayyappa Kauthuvam, fourteen varnams, six jatiswarams, ten

padams, twenty stutis and bhajans, eight Tillanas and nine dance dramas- Padmavathi

Kalyaanam, Bhakta Aiyyappan, Silapadhikaram, Dasaavataram, Gajendra Moksham,

Navarasa Ramayanam, Bhakta Meera, Kuravanji, and Sankshepa Ramayanam. All his dance

drams were performed live barring the last one “Sankshepa Ramayanaam” which was a

recorded production. His book of compositions for dance was published by his family in the

year 1995 titled “Bharata- Paamalai”. It contains most of his popular compositions. But

some more handwritten compositions have been found by his family which have not been

exposed to the public yet.

To keep abreast of the changing times, Guru Govindarajan changed the timing and format of

the varnams. The beautiful blend of tradition and contemporary demands was visible in his

style. Earlier, varnams would be performed for as long as four hours. But he kept his

compositions in tune with the pace of the audiences and narrowed down the varnams to crisp

thirty-minute renditions).

8.Common yet rare compositions:

a. Dasavataram:

Other than jatiswarams, padams, varnams, tillanas and several dance dramas, both the gurus

composed the “Dasavataram”, or the ten incarnations of Lord Vishnu in Ragamalika. Before

them, only 3 famous composers had written and composed them- poet Jaydev, Muthuswamy

Dikshidhar and Swati Tirunaal. This Keertanam is a significant contribution to the

Bharatanatyam repertoire to add variety and discourage repetition of the old items being

performed over many centuries.

b. Bharata Kalai:

They also created the “Bharata Kalai”, a rare composition praising the art of Bharatanatyam

dance.

Comparative analysis of their Bharata Kalai compositions:

Both Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai and Guru K J Govindarajan created compositions that

pay homage to the grandeur and spiritual depth of Bharatanatyam, each reflecting their

distinct artistic philosophies and emotional sensibilities. Though united by their reverence for

the dance form and their mastery over its musical dimensions, their compositional styles

reveal nuanced differences in approach and aesthetic choices.

While both use the same talam, i.e., Aadi, Dandayudapanipillai composed it in Ragamalika

while Govindarajan composed it in Ragam Shivaranjani.

Dandayudapanipillai’s Bharata Kalai:

This item is set to Ragamalika (Charukesi, Saranga, Hamsanandi and Kannada), Talam Aadi.

Bharata Kalai, as elucidated by K N Dandayudapanipillai, encapsulates the profound

significance of the art of dance. It serves as a lyrical ode to the universal reverence for dance,

portraying it as an integral aspect of life itself. Through simple yet profound lyrics, the song

expounds on the transformative power of dance, its ability to evoke joy, and its capacity to

convey a myriad of emotions without uttering a single word.

The song begins by asserting that dance is universally respected, transcending cultural and

societal boundaries. It emphasizes that dance should be revered as a fundamental aspect of

human existence, akin to the very essence of life. Through dedicated practice, dancers sculpt

their physical beauty, transforming their bodies into vessels of strength and power. The

repetitive practice not only hones their skills but also instils discipline and resilience,

moulding them into embodiments of grace and poise.

Furthermore, the song highlights the importance of music in dance, highlighting its role in

evoking instinctive facial expressions. When paired with suitable songs, dancers effortlessly

convey emotions, captivating the hearts of onlookers and replacing any concerns with sheer

delight. The emphasis on tasteful costumes and pleasant facial expressions emphasises the

importance of aesthetics in enhancing the overall experience of dance.

Moreover, the song extols the virtues of obedience and respect towards teachers, stressing the

role of guidance and mentorship in the dancer's journey. By adhering to the teachings of their

mentors, dancers can navigate the complexities of life and emerge victorious, both on and off

the stage.

In addition to its aesthetic appeal, dance serves as a powerful medium for expression, capable

of conveying a wide range of themes and emotions. The song celebrates the versatility of

dance, depicting its ability to articulate love, transcendental experiences, and spiritual

revelations without the need for verbal communication. Through intricate hand gestures and

expressive eye movements, dancers breathe life into ancient myths, scriptures, and tales of

divine beings, enriching the cultural tapestry of humanity.

Furthermore, the song acknowledges the universality of dance, transcending boundaries of

class, status, and fortune. Whether depicting the struggles of the impoverished or the

opulence of the affluent, dance offers a platform for storytelling and introspection. From the

scholarly pursuits of the wise to the artistic endeavours of the creative, dance celebrates the

diversity of human experiences.

In essence, Bharat Kalai embodies the essence of dance as a universal language, capable of

transcending socio-emotional barriers and uniting humanity in joy and celebration. It serves

as a testament to the enduring power of art to uplift, inspire, and enrich the human

experience, reaffirming the timeless relevance of dance as a cherished form of expression and

cultural heritage.

Govindarajan’s Bharata Kalai:

Bharat Kalai, as elucidated by KJ Govindarajan sir, epitomizes the essence of Bharatanatyam,

a classical dance form that has enchanted audiences for centuries. This ancient art form,

rooted in the rich cultural heritage of India, transcends mere entertainment, offering a

profound experience of joy and spiritual elevation to its spectators.

The lyrics and meanings of Govindarajan’s Bharat Kalai encapsulate the multifaceted beauty

of Bharatanatyam. As spectators witness the graceful movements and expressive gestures of

the dancers, they are enveloped in a sense of profound happiness. This dance form,

characterized by its intricate footwork, emotive storytelling, and rhythmic precision,

captivates the hearts of all who behold it.

K J Govindarajan explains that the illustrious poet Elango Adigal extolled Bharatanatyam in

his epic 'Silappadikaaram', highlighting its integration of poetry, music, drama, and dance.

This confluence of artistic elements evokes a harmonious symphony that resonates deeply

with the human spirit. The ancient Tamil text speaks of the grammar of dance, emphasizing

the meticulous craftsmanship and artistic finesse required to master this sacred art form.

He reiterates that throughout history, Bharatanatyam has been revered and enjoyed by people

from diverse backgrounds. The Moovarum, comprising the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas,

delighted in the splendour of this art form, recognizing its cultural significance and aesthetic

allure. Even the celestial beings, the Devas, were enraptured by the divine dance of Lord

Shiva, whose cosmic movements inspired the creation of Bharatanatyam.

He elaborates that Mukkannan, the embodiment of Lord Shiva with his third eye, bestowed

upon humanity the gift of Bharatanatyam. This art form, characterized by its fusion of bhava

(expression), raga (melody), and talam (rhythm), serves as a medium for spiritual

transcendence and artistic expression. It is a testament to the divine beauty inherent in the

human form, a celebration of life's rhythms and emotions.

Moreover, his Bharata Kalai emphasizes the inherent grace and elegance of Bharatanatyam,

particularly when performed by female dancers. Their fluid movements and emotive

expressions imbue the dance with a sense of sublime beauty, reminiscent of the gentle sway

of a blooming flower in the breeze.

In essence, Govindarajan’s Bharata Kalai is a testament to the eternal allure and

transformative power of Bharatanatyam. It is more than just a dance form; it is a sacred art

that illuminates the soul and uplifts the spirit, leaving a lasting imprint on the hearts of all

who encounter its mesmerizing splendour.

9. The Untimely Demise of the Two Artistic Luminaries:

Tragically, both Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai and Guru K J Govindarajan, who were

diabetic as well, departed this world far too soon, each succumbing to heart attacks that cut

short their lives devoted to the pursuit of art. Guru Dandayudapanipillai left us at the age of

fifty-three, leaving behind his second wife, Chandra, and his adopted daughter, Uma. Guru

Govindarajan passed away just six months before his sixtieth birthday survived by his wife –

also named Chandra, and their four children: Vasu, Elangovan, Raghu, and Vani. In a

testament to their enduring influence, the children of both Gurus remain deeply immersed in

the arts, continuing to uphold and expand the legacies their fathers so passionately built.

Both Gurus departed while fully engaged in their craft – Dandayudapanipillai while

conducting a performance, and Govindarajan while rehearsing for one. Their final moments

were spent in the very rhythm and spirit that defined their lives.

The legacies of Guru K N Dandayudapanipillai and Guru K J Govindarajan continue to echo

through the corridors of Bharatanatyam, not merely as historical footnotes but as living,

breathing inspirations for generations of dancers. What they left behind is not merely

memory, but a living archive of compositions, choreographies, and teachings that continue to

inspire dancers, musicians, and teachers across generations. Their ability to transcend artistic

boundaries and cultural shifts through the sheer creativity of rhythm and rasa is a testament to

their genius. As we revisit their life journeys, contributions and teachings, we are reminded

that true art does not conform – it evolves, adapts, and speaks directly to the soul. In

honouring their contributions, we not only preserve tradition but also nurture the creative

flame that drives Bharatanatyam forward into new realms of expression and emotional

resonance.

References:

Dance Dancers and Musicians: Collected writings of Nandini Ramani. (2011). [English]. Dr.

V. Raghavan Centre for Performing Arts.

Rajagopalan, H. (2016, March 26). K. N. Dandayudhapani Pillai Baani. Narthaki- Gateway

to the World of Dance. https://narthaki.com/info/profiles/profl193.html

Kothari, S. (1979). Bharata Natyam (1997th ed.) [English]. J.J. Bhabha for Marg

publications.

Obituaries. (2013). Narthaki.com.

Indian dance scene / "The River" 1951 (youtube.com)

Khokhar, A. (1994). Guru K J Govindarajan. First City Magazine.

Gaston, A.-M. (1997). Bharata Natyam: From Temple to Theatre [English]. Manohar

Publishers &

Distributors.

Govindarajan, K. J. (1995). Bharata Paamalai: “Natya Laya Gnana Isai Oli” Guru K. J.

Govindarajan. Bharata Natya Niketan (Regd) Publications.

Lineage http://www.umavasudevan.com/lineage

Vasudevan, U., & Vasudevan, G. (n.d.). Lineage. http://www.umavasudevan.com/lineage.

http://www.umavasudevan.com/lineage

Venkatraman, L. (2019). Epitomising the style & the totality of the teacher’s vision of a form.

Asian Age. In press.

Khokhar, A. (n.d.). Detail study of Bharatanatyam, Devadasis- nattuvanaar, Nritya and Nritta,

Different bani-s, Present Status, Institutions, Artists [English].

Vellat, A. (2018). The Guiding Light: Disciples of Bharatanatyam Guru KJ Govindarajan pay

homage to the master, who played a significant role in the growth of the dance form in

north India. The Hindu.

Krishnan, S. (2020, October). How grateful can one be for the stars. . . – Nritya Laya Darpan.

Facebook.

https://m.facebook.com/nrityalayadarpan/photos/a.1014471155233852/3869423646405241/?l

ocale=ms_MY

Facebook. (n.d.).

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=6750349988358988&set=a.624866914240690

Singh, S. S. (2000). Indian Dance: The Ultimate Metaphor [English]. Ravi Kumar, Publisher.

Subramaniam, P. V. (1980). Bharatanatyam. Samkaleen Prakashan.

Rajan, A. (2016, May 23). Guru’s grace. The Hindu.

https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/society/gurus-grace/article6510748.ece

TOP 25 QUOTES BY MARTHA GRAHAM (of 126) | A-Z quotes. (n.d.). A-Z Quotes.

https://www.azquotes.com/author/5783-Martha_Graham

Re: Meaning of song- Ulagam pugazhum. (n.d.).

https://narthaki.com/barchives/messages7/6090.html

Anand, U. (2021). Life & Contributions: Natayakala Chakravarthy K. N.

Dandayudapanipillai (2nd edition, 2021 centenary edition) [English]. Dr. Uma

Anand.